Traces of human and natural history

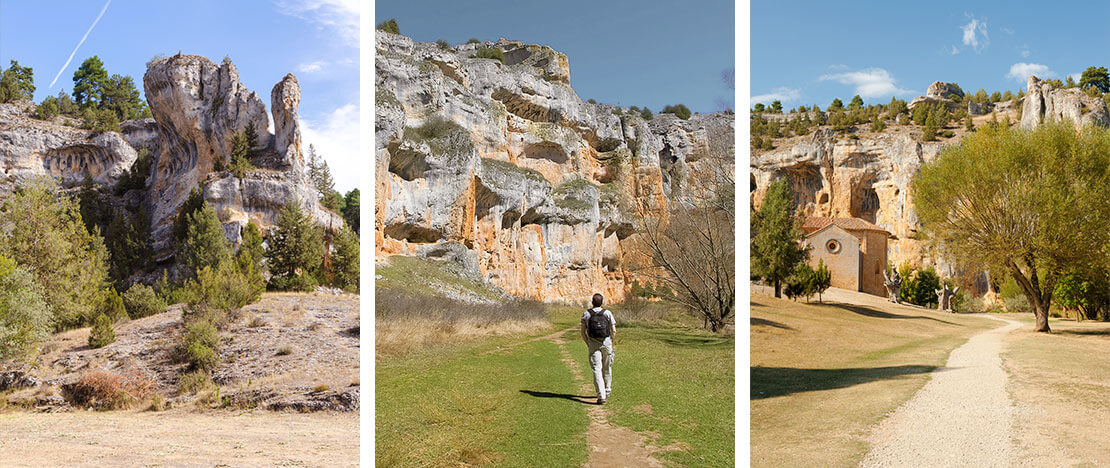

You can join this path from either end, or halfway along the trail at Siete Ojos bridge, where you can leave your car. But remember that as this is a linear trail, wherever you begin you will eventually have to turn around and go back. Along the way you’ll see landscapes of towering limestone cliffs up to 100 metres high.It’s fascinating to see how nature has populated the area with the fauna and flora typical of riverside ecosystems, and the sound of running water will accompany you as you walk along. The rocks reflect millions of years in their geology, and the terrain is very varied, with aquifers, caves, stalactites and stalagmites.

La Ermita de San Bartolomé: mysterious Templar symbolism

This country chapel, near the start of the path on the Soria side, is much more than the most important art-historical site on the trail. In the Romanesque and proto-Gothic style, it was built in the 12th century, and thought to have belonged to the Knights Templar. The beautiful doorway, the rose window with esoteric figures, the Templar cross, and the three hundred-year-old elm trees standing over it, conjure up a magical scene.

There are many stories and legends associated with it. They say the site was chosen when Saint Bartholomew leapt from his horse on the mountaintop and flung his sword into the valley, with the cry “Where my sword lands will be my home.” This area also connects to the French Way, one of the pilgrimage routes making up the Camino de Santiago, and it may have been a lay brotherhood of pilgrims (the Hijos del Maestro Santiago) who built the chapel.Very close by, the Cueva Grande is a cave with prehistoric art. You can also climb up to “El Balconcillo”, a natural rock window with unforgettable views over the gorge.

Other stops along the way

There are several more places along the trail worth taking a break to see. After the Ermita de San Bartolomé is a curious sight known as Colmenar de los Frailes, where old beehives made from tree-trunks are perched on the rock.Castillo Billido is an ancient Celtiberian castro and a natural viewing point.Further on, there are several caves in the canyon, including Cueva Negra, home to one of Spain’s largest birds, the Eurasian eagle-owl. Nearby, the watering place at Pozo Perín attests to the importance over the centuries of transhumance: moving grazing herds to seasonal pastures. The caves and hollows of the canyon provided shelter for shepherds taking their flocks along the trail known as Cañada del Mojón Blanco.

Halfway along the trail crosses a bridge, Puente de Siete Ojos, and then continues upstream through other areas, including Risca Fría, where you can usually spot the silhouettes of large birds of prey in the sky, and El Apretadero, where the gorge narrows.And near the end of the path, you come to Chozo de los Resineros, distinguished by the marks on the trees around you. This is an area where local artisans used to come to extract natural resins from the trees.

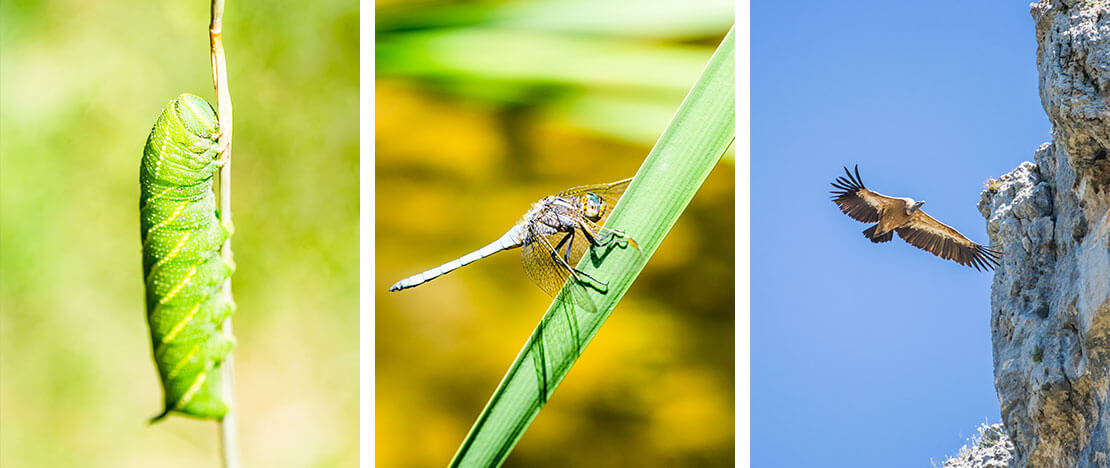

Wildlife of water, earth, and air

As parts of the river dry out in summer, almost all the wildlife lives on the riverbank and in the highest points. Depending on the time of year and how quiet you are, you may spot roe deer, otters, bats, and hares, as well as reptiles and amphibians. If you look carefully at the yellow waterlilies that cover much of the river, you’ll see Perez's frog, also known as the Iberian green frog, and viperine water snakes.

And if you look up, thanks to the geology of the canyon, one of the most common birds here is the griffon vulture. But other birds of prey also live and hunt here, including golden eagles, Egyptian vultures, common kestrels, and peregrine falcons.Almost all the shade comes from hundred-year-old poplars and willows which grow a few metres from the river. You’ll also find typical plants like great willowherb, yew, and stork's-bill.